Proust has not been well served by portraitists. Perhaps the most insipid is by Jacques-Émile Blanche, yet it is reproduced everywhere. May I propose a somewhat improved and less well-known version? This is Portrait of Proust 1950 by Richard Lindner:

Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

Proust Portraits

February 11, 2015The Careful Reader

July 28, 2014Towards the end of The Fugitive, Proust drops a little bombshell that has startled many careful readers of the novel. It occurs in a passage where Proust is addressing the relationships involved in two weddings, that of Jupien’s daughter to the Cambremers’ son and Gilbert to Robert de Saint-Loup:

Yet another mistake which any young reader not acquainted with the facts might have been led to make was that of supposing that the Baron and Baronne de Forcheville figured on the list in the capacity of parents-in-law of the Marquis de Saint-Loup, that is to say on the Guermantes side. But on this side they had no right to appear since it was Robert who was related to the Guermantes and not Gilberte. No, the Baron and the Baronne de Forcheville, despite these deceptive appearances, did figure on the wife’s side, it is true, and not on the Cambremer side, not because of the Guermantes, but because of Jupien, who, the better informed reader knows, was Odette’s first cousin. (V,915)

I had noted this curious passage on a post long ago without knowing what to make of it. Had this this curious cousin relationship been mentioned earlier in the novel and we had missed it? Or was Proust introducing a theme here that he did not have time to develop? It came to my attention again on the Goodreads Year of Reading Proust group site. Alert reader Inderjit wondered if he had missed something. Indefatigable reader Marcellita Swann pointed him to my post, which I’m afraid does not add much. I Googled the passage to see if anyone else had any insight. I didn’t find anything except for an alternate translation of the passage. In the original Scott Moncrieff Modern Library edition, the passage is: “...the reader must now be told…”, which would favor the undeveloped theme explanation. So, is this is a translation issue, with Kilmartin changing the phrase to “the better informed reader knows“? But which is the better translation?

Marcellita marshaled her resources and received from Bill Carter the Pleiade original: “Jupien, dont notre lecteur plus instruit sait…”. It seems then that Kilmartin is closer to the original, “better informed” for “plus instruit.” Further, her source James Connelly mentions “The notes indicate that he reminded himself to develop this with an unknown character, Rigaud, but death intervened.” :

Albertine Disparue (The Fugitive) definitely feels unfinished. Like the last 3 volumes of La Recherche it was published posthumously (and edited by Marcel’s brother, Robert Proust, and Jacques Rivière from Gallimard). We can only imagine what a few more years would have allowed Marcel to write, probably adding a few more volumes in the process.

There is consequently no definitive text of Albertine Disparue. In 1986 a Proust heir unveiled a “dactylographie” where Proust had removed about 150 pages of the text, leading to a new, shorter version of Albertine, which was even less satisfying… More on this here (in French):http://www.fabula.org/cr/412.php.

Re Odette & Jupien’s relationship, it was never mentioned before this passage. My sense is that Marcel talks of “notre lecteur plus instruit” (our better informed reader) by opposition to the younger people (“les jeunes gens des nouvelles générations” and “tout jeune lecteur”) who do not know precisely the complex genealogy of the aristocraty, pleasantly assuming that his reader (“notre lecteur”) knows all this as well as he does.

This seems the best answer. Proust juxtaposes The “well-informed reader” to the “young reader”, which occurs both in this paragraph and a couple of pages earlier. This section of The Fugitive titled “New Aspect of Robert de Saint-Loup” deals with the constant regeneration of society. The young contemporaries just beginning to move about society tend to see the current order as fixed and ancient. Proust counters with the stories of the elevation to nobility of a tailor’s daughter to the titled Mlle d’Oloron and her marriage to the son of the engineer’s daughter and nephew of the self-styled Legrandin de Meseglise (later self-enobled to Comte de Méséglise), the Marquis de Cambremer. And with the marriage to the genuine noble Robert de Saint-Loup to the daughter of the coquette Odette.

Proust developed these histories in the way described by Book Portrait, as a comparison of the views of the young and naive to those of their better informed elders: “…but many young people of the rising generation..” (V,913) and repeated in “Yet another mistake which any young reader not acquainted with…” to their more knowledgeable elders “the better informed reader…”.

But the earlier explanations we came up with still holds merit. Scott Moncrieff, by changing “better informed” to “the reader must now be told” obscures, if not entirely hides, Proust’s parallel construction. And Connelly is surely correct in saying that Proust intended to further develop the Jupien-Odette cousin story.

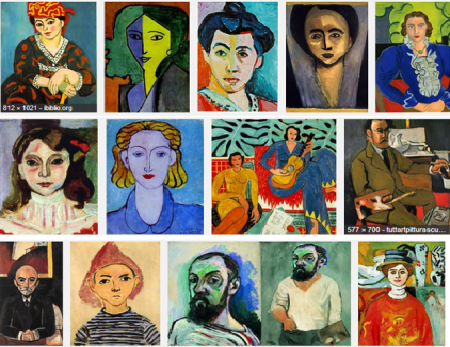

The Richardson Proust Portraits

December 9, 2013David Richardson has recently published the portraits of many of the characters appearing in ISOLT. The book is a limited edition (translation: very expensive) and the production quality is very high. Richardson is a vibrant colorist, recalling to my mind the portraits of Matisse. I have copied a few random portraits from each artist for you to make the comparison.

(The book, as well as individual prints, is available at http://www.davidwesleyrichardson.com/order/)

- Selected Matisse portraits (Google Image Search)

Richardson:

Richardson Proust portraits taken from http://www.davidwesleyrichardson.com/resemblance/

The Madeleine Stories

January 21, 2013The title of Anka Muhlstein’s new book, ‘M. Proust’s Library’, at first struck me as odd, since Proust did not have much of a book collection. Proust seems to have committed large sections of whatever he read to memory, making the ownership of books superfluous. But she has the wider meaning of library in mind. One of her threads helped me to better way frame the famous madeleine incident.

Proust’s Search can actually be condensed quite a lot once we ignore all the Marcel flashback stuff. A middle-aged man, in anguish over how to become a writer, has a pleasant glow of reminiscence after the taste of a pastry dipped in warm tea creates a kind of space-time wormhole to his childhood. But the glow fades. He takes a walk in the Bois in order to bring back more of these unforced memories. The walk ends in gloom as he is reminded simply of the loss of beauty in his life. He visits a childhood friend—but their conversations do not show him a way forward as an artist. He commits himself to some sort of asylum for renewal, which he interrupts to take a short trip to Paris during the war years. He sees startling events, but still cannot figure out how to knit them together into a narrative. Years later he returns to Paris again and accepts an invitation to a soirée filled with characters he had known throughout his childhood and youth. It is here that everything changes.

Muhlstein writes about the moment of his artistic self-discovery:

At the very end of the novel, the Narrator suddenly sees François le Champi on a shelf in the Prince de Guermantes’s library, and the mere sight of the volume triggers the memory of “the child I had been at that time, brought to life within me by the book, which knowing nothing of me except this child it had instantly summoned him to its presence, wanting to be seen only by his eyes, to be loved only by his heart, to speak only to him. And this book which my mother had read aloud to me at Combray until the early hours of that night… [A] thousand trifling details of Combray which for years had not entered my mind came lightly and spontaneously leaping, in follow-my-leader fashion, to suspend themselves from the magnetized nib in an interminable and trembling chain of memories… [and re-created] the same impression of what the weather was like then in the garden, the same dreams that were then shaping themselves in [my] mind about the different countries and about life, the same anguish about the next day.” George Sand is the only writer Proust read as a child whom he comments upon in La Recherche…. (pages 7-8)

So this book-inspired unforced memory, about a country waif adopted by (and later married to) a woman named Madeleine, is the more powerful of the madeleine stories, touching as it does not only on Marcel’s artistic breakthrough and its source in literature, but also Proust’s deepest psychological nature.

On Reading Difficult Literature

October 27, 2012Gary Gutting, a philosopher who contributes to the NYT blog The Stone, has written an insightful piece on what it means to read difficult literature. He explores the ideas behind our idea of “guilty pleasure” reading, a notion that depends on two assumptions: “that some books (and perhaps some genres) are objectively inferior to others and that “better” books are generally not very enjoyable.” He notes that the latter category generally includes Proust.

But many intelligent, widely-read people do not like Proust, so does that make literary tastes completely relative? Perhaps to a degree, but whatever genre we read we each have standards about who are the better writers. Gutting himself finds “In Search of Lost Time” “a magnificent probing of the nature of time and subjectivity…”. Others find Proust, Joyce, Eliot wilfully obscure.

The deeper question is why we find difficulty a barrier to reading. Many of us, after all, will run a marathon, endure the pain and then call it fun. That said, I think most readers who get past the first passages find Proust enjoyable. Still, you will encounter pain. At some you point you will wish that Albertine slap Marcel in the face and bring him to his senses. Gutting concludes, “But the sign of a superior text of whatever genre is its ability to continue rewarding—with pleasure—those who work to uncover its riches.”

2013: The Year of Reading Proust

September 4, 2012I have recently learned of a Proust reading group that begins the novel next year. It should be a good opportunity to read the novel with many supportive readers. http://www.goodreads.com/group/show/75460-2013-the-year-of-reading-proust

Hume and Bondage

December 12, 2011I don’t know how familiar Proust was with Hume, but he certainly shares his view that the intellect without the desires is nothing. http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/12/11/of-hume-and-bondage/?hp

Goddess of Time

January 19, 2011Howard Moss, in his The Magic Lantern of Marcel Proust, provides these vignettes of Marcel’s three lovers.

These three loves, though they are all failures, differ from each other in important ways. Marcel gives Gilberte up as if the suffering his love for her entails is too much to bear. He protects that love by refusing to allow it to be nurtured toward a conclusion; he draws back to avoid further pain. Haunted by doubt, doubt becomes obsessive. It is only late in life that he realizes that Gilberte was attainable. She confesses she was attracted to him, at the very end of the novel. At the time their relationship takes place, he withdraws in order to sanctify the image of his love rather than risk its failure. In this retreat, we have a narcissistic, almost masturbatory version of love. The picture, or image of the beloved, is more precious than its actual presence–just as the lantern slides of Geneviève de Brabant are always to be the ideal against which the Duchesse de Guermantes is to be measured. So the idealization of women–like places–is always fatally inconsistent with knowing them. Like the two ways, where geography becomes mental, so, here, physicality and personality become internalized. The true Gilberte exists inside Marcel, not outside him. Marcel destroys and preserves his relationship to her at the same time. Oblivion accompanies separation. But by not coming to any issue, the relationship forms an unconscious pattern for those of the future, as it reinforces the emotional patterns of his behaviour toward women that began with his mother. If love can be deliberately demanded, it also can be deliberately killed.

Mme. de Guermantes inspires love by awe; her name is evocative, magical. She is not a person who turns into an illusion like Gilberte, or an illusion that turns into a person like Albertine. She is inhuman to begin with. Proust says that the love for a person is always the love of something else as well, and, in the Duchesse, Marcel becomes obsessed with the power of the feudal overlord who is still a member of the contemporary world–a world so select, so special, that, to Marcelo, it might as well be the Middle Ages. If, with Gilberte, he falls in love with the legend of Swann, with the Duchesse, he falls in love with the history of France. It is not her wit, her style, her position, or her beauty that ultimately matter; it is that in her name she embodies a history; in her face and person a race; in her speech a landscape and an epoch; and in her manners a civilization. Though her intelligence, her modishness, her ton impress everyone as they do herself, to Marcel, after he has sifted the real jewels from the fake, it is another quality that counts: her conservativeness, in the real sense, for here, in person, is the prototype of something worthy of conservation. The Duchesse, the greatest lady of her day, and Françoise, the servant, share qualities in common. Their speech and their manners are feudal; the serf and the lord possess virtues enhanced by the existence of each other. The farmer and the landowner, still bearing the fragrance of the soil, enrich each other’s powers. In Remembrance of Things Past, Françoise and the Duchesse have no reason to meet. Yet they have more in common than either could possibly imagine. They are two terms that have become separated in one of Proust’s metaphors. (34-36)

Who is Albertine? She is the unknowable animal who calls forth the finest resources of Marcel’s intellect. The greatest analytical mind in the world is helpless confronted with a dog. It is Marcel’s fate to want to see what cannot be seen: the sex life of a plant, the emotional histories of the deep-sea creatures, the motivations of the dark. Marcel and Albertine are two liars hopelessly tangled together. She charms him by being out of the range of what analysis can reach. To keep her in focus for a further try, lured by what he cannot know, he falls in love with her.

Albertine is Marcel’s sensibility turned inside out and objectified. The greater pretense in their relationship comes from Marcel. Her reserve in the face of his jealousy, her lies, her restlessness, all prod him on to another attack. If he knows, he keeps saying, he would be happy. But it is precisely because he doesn’t know that he loves her. A scientist in a dressing gown, he watches over a laboratory of falsehoods, the greatest one being that he is objective in regard to the truth. Marcel uses Albertine to keep from himself a truth about himself: he is not in love with Albertine, he is in love with what Albertine loves.

As such, he credits her with a power and a reality she doesn’t have. Albertine is addicted to games–particularly “diabolo”–clothes, cars, ice cream, planes. She is far simpler than he and far more deceptive. His lies are lies of the mind, hers of being. In Albertine, Marcel is matched against himself in a battle that cannot be finished. She holds within herself the two sexes in one and is, therefore, a constant reenactment in her very existence of the ideal torture of the voyeur. Albertine is the window scene of Montjouvain, the courtyard scene of Charlus and Jupien played over for ever and ever.

It is no wonder that her commonest attributes, her polo cap, her macintosh, the way she plays the pianola, her stride along the front–every physical manifestion of herself–takes on an Olympian sheen. Marcel grasps at every vestige of her reality because he has made her up the way the Greeks made up their gods: he needs constantly to be reassured that she is there. Albertine is both a deity in Proust’s “Garden of Woman” and the demon at the center of his vision, for he describes her as “a mighty Goddess of Time” under whose pressure he is compelled to discover the past. Starting out with the mystery of the animal, she ends up with the mysteries of eternity. (39-41)

Axel’s Castle II

November 7, 2010Proust famously denounced attempts to reduce art to the person of the artist. The self that makes art is not the self that we engage socially. Still, this leaves room to read the novel to understand the artist’s self. Wilson does this and does not like who he meets.

The fascination of Proust’s novel is so great that, while we are reading it, we tend to accept it in toto. In convincing us of the reality of his creations, Proust infects us with his point of view, even where this point of view has falsified his picture of life. It is only in the latter part of his narrative that we begin seriously to question what he is telling us. Is it really true, we begin to ask ourselves, that one’s relation with other people can never provide a lasting satisfaction? Is it true that literature and art are the only forms of creative activity which can enable us to meet and master reality? Would not such an able doctor as Proust represents his Cottard as being enjoy, in supervising his cases, the satisfaction of knowing that he has imposed a little of his own private reality upon the world outside? Would not a diplomat like M. de Norpois in arranging his alliances?–or a hostess like Mme. de Guermantes in creating her social circle? Might not a more sympathetic and attentive lover than Proust’s hero have even succeeded in recreating Albertine at least partly in his own image? We begin to be willing to agree with Ortega y Gasset that Proust is guilty of the mediæval sin of accidia, the combination of slothfulness and gloom which Dante represented as an eternal submergence in mud.

For “A la Recherche du Temps Perdu,” in spite of all its humor and beauty, is one of the gloomiest books ever written. Proust tells us that the idea of death has “kept him company as incessantly as the idea of his own identity”; and even the water-lilies of the little river at Combray, continually straining to follow the current and continually jerked back by their stems, are likened to the futile attempts of the neurasthenic to break the habits which are eating his life. Proust’s lovers are always suffering: we scarcely ever see them in any of those moments of ecstasy or contentment which, after all, not seldom occur even in the case of an unfortunate love affair–and on the rare occasions when they are supposed to be enjoying themselves, the whole atmosphere is shadowed by the sadness and corrupted by the odor of the putrescence which are immediately to set in. (164-165)

And so with Proust we are forced to recognize that his ideas and imagination are more seriously affected by his physical and psychological ailments than we had at fist been willing to suppose. His characters, we begin to observe, are always becoming ill like the hero–an immense number of them turn out homosexual, and homosexuality is “an incurable disease.” Finally, they all suddenly grow old in a thunderclap–more hideously and humiliatingly old than we have ever known any real group of people to be. And we find that we are made more and more uncomfortable by Proust’s incessant rubbing in of all these ignominies and disabilities. We begin to feel less the pathos of the characters than the author’s appetite for making them miserable. And we realize that the atrocious cruelty which dominates Proust’s world, in the behavior of the people in the social scenes no less than in the relations of the lovers, is the hysterical sadistic complement to the hero’s hysterical masochistic passivity.What, we ask, is the matter with Proust?–and what is it that happened to his novel? (165-166)

It seems to me plain, in spite of all the rumors as to the ambiguity of Albertine’s sex, that both Proust’s hero and himself were exceeding ly susceptible to women: we are certainly made to feel the feminine attraction of both Albertine and Odette, and the spell of their lovers’ infatuation, whereas, on the other hand, none of the male homosexual characters is ever made to appear anything but horrible or comic. Proust had apparently, in his youth, been in love at different times with several women–Mme. Pouquet was evidently one of these–had fared rather badly with them and had never forgiven them to the end of his days. And he shows in “A la Recherche du Temps Perdu” more resentment against the opposite sex than enthusiasm for his own. Homosexuality figures in Proust almost exclusively under the aspect of perversity, and it is in general unmistakably associated, as in the incident of Mme. Vinteuil, with another kind of perversity, sadism. The cruel and nasty side of Proust is the inevitable reaction against, the inevitable compensation for, the good-little-boy side which…was a great deal too good to be human–or, more precisely, which remained rather puerile. (181-182)

Proust was never able to find any other woman to care for him as his mother did. His friends have testified to the fact that it was impossible for any friend or inamorata to meet the all-absorbing demands for sympathy and attention which he was accustomed to having satisfied at home; and he was unwilling or unable to make the effort to adjust himself to any non-filial relation. The ultimate result was that strange state of mind which often disconcerts us in his novel: a state of mind which combines a complacent egoism with a plaintive malaise at feeling itself shut off from the world, a dismay at the apparent impossibility of making connections with other human beings. We end by feeling that, after all, he enjoys the situation of which he is always complaining. Did he not prefer, after all, his invalid’s cell, with his mother ministering to him, to the give and take of human intercourse? The death of his mother upset this situation and we probably owe his novel to it. Proust, with his narcotics, his fumigations, his cork-lined chamber, his faithful servants and his practice of sleeping all day, arranged for himself an existence as well protected as it had been during his mother’s lifetime; but lacking that one human relationship which had sustained him, he was obliged to supply something to take its place and for the first time he set himself seriously to work. His need now to rejoin that world of humanity from which he had allowed himself to be exiled become more pressing, and his book was a last desperate effort to satisfy it. (183-184)

William C. Carter Proust Lectures

September 4, 2010William C. Carter, author of Marcel Proust: A Life, will be delivering a 30 part online lecture series on Proust and ISOLT beginning Sept. 15, 2010. See the details of the course, cost and registration at his web site http://proust-ink.com.